I want to tell you a story.

It’s a story about a man I met in a café years ago, a man who had recently lost his father. But in order to understand what passed between us, I first need to tell you a completely different story which appears as part of a show I perform called “Can the Mountains Love the Sea?”. The show is an hour of myth drawn from the Scandinavian Eddas, which were first written down some eight hundred years ago. It follows the life of a giantess called Skathi and her various adventures and interactions with the Gods and Goddesses that make up the Norse pantheon. The show is funny, rude in places, fierce in others. Towards the end a mood of Viking fatalism takes over. In one scene, Frigg, a Mother Goddess, visits Skathi, the fierce giantess. Frigg’s beloved son, Baldur, has died and in her grief she has ridden into the Lands of the Dead to meet with their Queen and beg for her son to be returned to life. The Queen of the Dead makes Frigg a once-in-eternity offer. It’s claimed that because of Baldur’s beauty and kindness, he is loved by all beings – if Frigg can persuade every living thing to cry for Baldur, all at the same time, then just this once the contract of life and death will be undone and Frigg can have her son back.

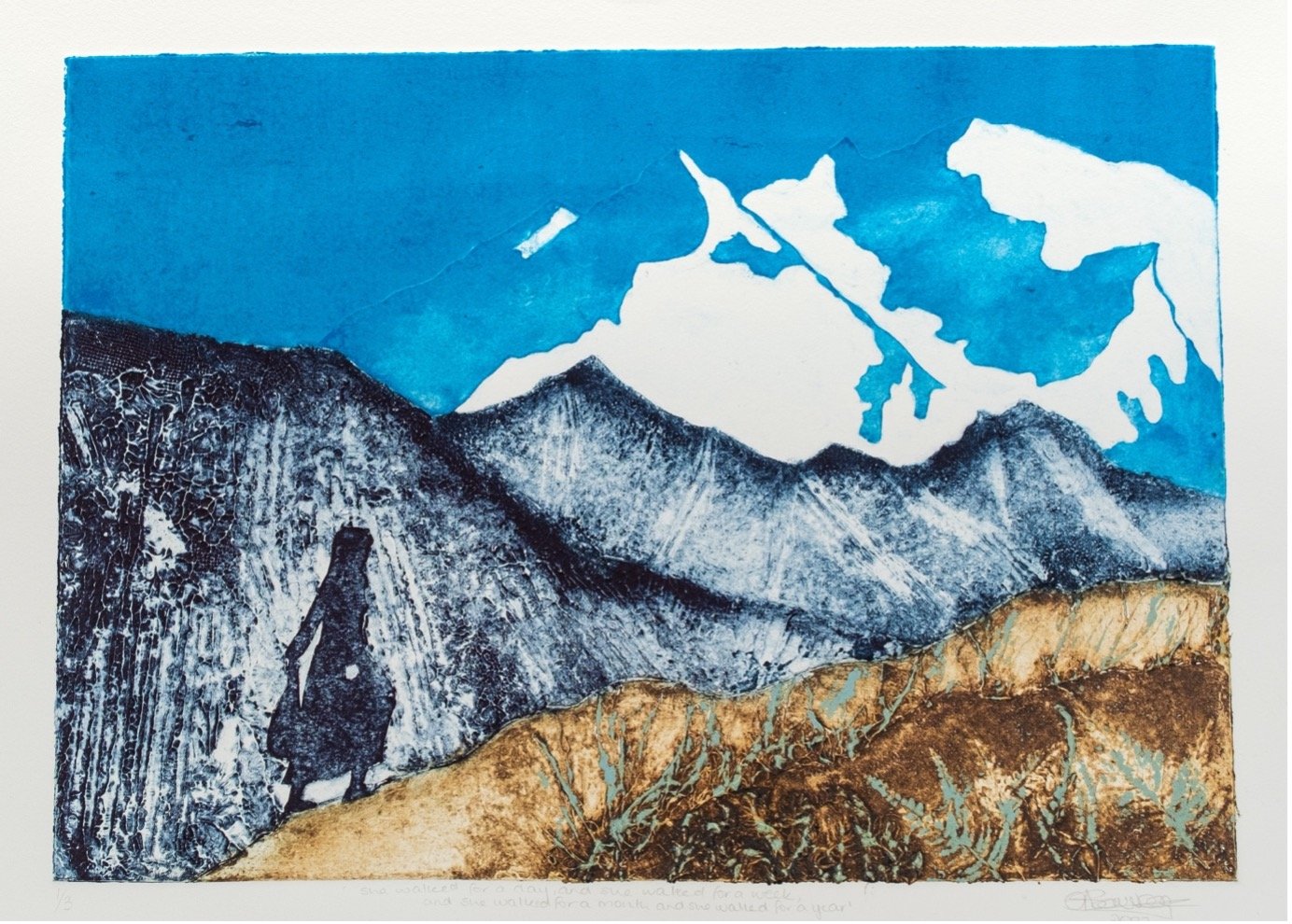

Frigg beseeches the giantess: will she cry for Baldur, her lost son, so that he might be restored to life? Of course Skathi agrees and that night she steps out from her remote mountain home, kneels on the rocky ground and begins to weep. She cries for Baldur, and for Frigg’s grief. She cries as she thinks of her own father, who she lost years before. She cries for everyone who has ever lost someone they cared for. As she weeps, she becomes aware that the world is weeping. Nearby birds have stirred from their roosts to mourn, the trees on which they perch are shedding tears of sap, the tufts of grass around are crying the morning dew. Even the stars up ahead, blurred and sparkling, join in the shared grief, shedding their light in collective sorrow. The world pauses, united in love and grief.

It doesn’t work, but that’s another story.

When I tell stories, I’m acutely affected by the context in which the telling takes place. When I brought that show to Northampton, the telling took place in a dark studio in the basement of The Royal and Derngate Theatre. In that setting, the show was a performance. I was there as an entertainer. I leaned into the jokes and ribaldry of the first half, knowing that it would give much needed contrast to the emotional impact of the end of the show. An hour passed. The audience applauded politely and shuffled out. They seemed adequately entertained. My job was done.

It was a few months later that I was back in Northampton for something completely unrelated. I was in an upstairs room of a café when a young, thick set man approached me, an air of urgency about him. He told me he’d been at the theatre that night, he’d heard the stories. He went on to explain that since then, his father had died. I offered my condolences but he brushed them off – there was something he needed to tell me. He talked about how, after the funeral, late at night, he’d been driving home when it started to rain. All at once he’d felt moved to stop the car and get out.

“It was like in the story,” he said. “It was like the whole world was crying. And that made sense, because everyone loved Dad.”

He seemed calmer after speaking. He’d fulfilled something, shared something important to him. We’ve never seen each other again.

There is a dignity in not over-analysing something like this, so I don’t want to dwell on this young man and his relationship to a moment in a story. For myself, I was left with a sense of privilege at our exchange. It was a reminder of the power of mythic imagery: that these stories can provide a framework or interior language for understanding and experiencing the flow of our lives.

In “A Short History of Myth,” author and former nun, Karen Armstrong, writes:

“…in the pre-modern world, when people wrote about the past they were more concerned with what an event meant. A myth was an event which, in some sense, had happened once, but also happened all the time. Because of our strictly chronological view of history, we have no word for such an occurrence, but mythology is an art form that points beyond history to what is timeless in human existence, helping us get beyond the chaotic flux of random events, and glimpse the core of reality.” — Karen Armstrong

We are creatures who live and comprehend the world inside time and so our stories are necessarily rooted in a particular chronology. This thing happened, then that thing happened. But mythic time isn’t like that. It is happening right now and it is always happening. We can get a sense of this when watching a performance, a film, or reading a book that takes us into a liminal state, that immerses us. Suddenly the world of the story seems more urgent, more immediate, more real than the everyday world we usually live in. It can be interesting to note what happens to us when such an experience is over. Do we return to a world that feels grey and flat, with a feeling of being disassociated from it? Or do we return enlivened, energised, more open to noticing the rich variety of the world and with a deeper capacity to be present to our surroundings? My belief is that it’s more often the latter. Moreover, because myth deals with profoundly universal themes like loss, love, family, rage, and so forth, the raw material of myth remains endlessly relevant. Sooner or later the normal course of our lives will be disrupted, but the shapes and structures of myth can provide a vital container to hold the inner chaos.

Psychologist James Hillman makes an even bolder claim regarding myth when discussing the potential limits of talking therapy. He invites us to reframe the disruptive experiences of our lives as initiatory. This approach allows us to recontextualise our personal history as taking place in a “…context of many, many mythological acts, some brutal, some beautiful. … This means its significance can always change. It’s a place where literal life and mythical life meet. That’s where wounds are.”

This invitation, which frames myth and the imaginal not just as vehicles for understanding but as worlds in which we can actively participate, carries with it the possibility to look again at our experiences in a way that makes them both more meaningful but also less personal to us as individuals. This practice does not take us on a purely interior journey but allows us to connect more broadly with both the human and beyond human world. To return to the story of the young man who had lost his father, his bereavement was a gateway that enabled him to participate in the grief of the world. It united him with a loss that was being felt in the weather, the land, and by divine characters from across time.

What can we do if we’re interested in exploring myth in this way? On a simple level, we can deliberately and consciously seek out stories that move and inspire us. We can nourish our creativity so that our capacity for a diverse and vivid imagination is increased. At the very least, we’ll probably have fun in the process. If we want to approach things in a more considered way it’s worth taking stock of our own inner repertoire. What are the stories we know? Do they follow particular shapes or have patterns that play out consistently? We can then begin to explore whether there are gaps in our inner repertoire either by looking for themes that seem absent or by areas of our life that feel incomprehensible. For me, these are processes that are often more effective in dialogue and conversation. A story or an idea can be passed back and forth, different perspectives revealing hidden depths and alternate possibilities, creating a sense of mutual support, comradeship and community as we practice together.

My faith in the role of the imaginal in our personal and spiritual journey has been a major influence in developing the “Story, Self, and Spirit” course that returns this Spring as part of OneSpirit’s portfolio of workshops. Meeting weekly online, with creative assignments in between, we’ll explore the role of story in creating our sense of self and begin to take a conscious approach to our autobiographical material. Myth and story from folk and faith traditions will underpin each session and will form a shared, supportive treasure house, from which we’ll be able to draw both during the course and hopefully for years to come.

The works referenced in this article are:

-

Karen Armstrong, “A Short History of Myth.” – Canongate

-

James Hillman and Michael Ventura, “We’ve had a hundred years of psychotherapy and the world’s getting worse.” – Harper San Fransico

~ Written by OneSpirit Guest Tutor, Tim Ralphs